Cambrian explosion

The Cambrian explosion or Cambrian radiation was the relatively rapid appearance, over a period of many million years, of most major Phyla around 530 million years ago, as found in the fossil record.[1][2] This was accompanied by a major diversification of other organisms, including animals, phytoplankton, and calcimicrobes.[3] Before about 580 million years ago, most organisms were simple, composed of individual cells occasionally organized into colonies. Over the following 70 or 80 million years the rate of evolution accelerated by an order of magnitude (as defined in terms of the extinction and origination rate of species[4]) and the diversity of life began to resemble today’s.[5]

The Cambrian explosion has generated extensive scientific debate. The seemingly rapid appearance of fossils in the “Primordial Strata” was noted as early as the mid 19th century,[6] and Charles Darwin saw it as one of the main objections that could be made against his theory of evolution by natural selection.[7]

The long-running puzzlement about the appearance of the Cambrian fauna, seemingly abruptly and from nowhere, centers on three key points: whether there really was a mass diversification of complex organisms over a relatively short period of time during the early Cambrian; what might have caused such rapid change; and what it would imply about the origin and evolution of animals. Interpretation is difficult due to a limited supply of evidence, based mainly on an incomplete fossil record and chemical signatures left in Cambrian rocks.

Axis scale: millions of years ago.

Stratigraphic scale of the ICS with Russian Lower Cambrian subdivision and Precambrian/Cambrian boundary.History and significance

Geologists as long ago as Buckland (1784–1856) realised that a dramatic step-change in the fossil record occurred around the base of what we now call the Cambrian.[6] Charles Darwin considered this sudden appearance of many animal groups with few or no antecedents to be the greatest single objection to his theory of evolution. He had even devoted a substantial chapter of The Origin of Species to solving this problem.[7]

American palæontologist Charles Walcott proposed that an interval of time, the “Lipalian”, was not represented in the fossil record or did not preserve fossils, and that the ancestors of the Cambrian animals evolved during this time.[8]

More recently it was discovered that the history of life on earth goes back at least 3,450 million years[9]: rocks of that age at Warrawoona in Australia contain fossils of stromatolites, stubby pillars that are formed by colonies of micro-organisms. Fossils (Grypania) of more complex eukaryotic cells, from which all animals, plants and fungi are built, have been found in rocks from 1,400 million years ago, in China and Montana. Rocks dating from 565 to 543 million years ago contain fossils of the Ediacara biota, organisms so large that they must have been multi-celled, but very unlike any modern organism.[10] P. E. Cloud argued in 1948 that there was a period of "eruptive" evolution in the Early Cambrian,[11] but as recently as the 1970s there was no sign of how the relatively modern-looking organisms of the Middle and Late Cambrian arose.[10]

The intense modern interest in this "Cambrian explosion" was sparked by the work of Harry B. Whittington and colleagues, who in the 1970s re-analysed many fossils from the Burgess Shale (see below) and concluded that several were complex but different from any living animals.[12][13] The most common organism, Marrella, was clearly an arthropod, but not a member of any known arthropod class. Organisms such as the five-eyed Opabinia and spiny slug-like Wiwaxia were so different from anything else known that Whittington's team assumed they must represent different phyla, only distantly related to anything known today. Stephen Jay Gould’s popular 1989 account of this work, Wonderful Life,[14] brought the matter into the public eye and raised questions about what the explosion represented. While differing significantly in details, both Whittington and Gould proposed that all modern animal phyla had appeared rather suddenly. This view was influenced by the theory of punctuated equilibrium, which Eldredge and Gould developed in the early 1970s and which views evolution as long intervals of near-stasis "punctuated" by short periods of rapid change.[15]

Other analyses, some more recent and some dating back to the 1970s, argue that complex animals similar to modern types evolved well before the start of the Cambrian.[16][17][18] There has also been intense debate whether there was a genuine "explosion" of modern forms in the Cambrian and, to the extent that there was, how it happened and why it happened then.[19]

Types of evidence

Deducing the events of half a billion years ago is difficult, as evidence comes exclusively from biological and chemical signatures in rocks and very sparse fossils.

Dating the Cambrian

Accurate absolute radiometric dates for much of the Cambrian, obtained by detailed analysis of radioactive elements contained within rocks, have only rather recently become available, and for only a few regions.[20]

Relative dating (A was before B) is often sufficient for studying processes of evolution, but this too has been difficult, because of the problems involved in matching up rocks of the same age across different continents.[21]

Therefore dates or descriptions of sequences of events should be regarded with some caution until better data become available.

Body fossils

Fossils of organisms' bodies are usually the most informative type of evidence. Fossilisation is a rare event, and most fossils are destroyed by erosion or metamorphism before they can be observed. Hence the fossil record is very incomplete, increasingly so, further back in time. Despite this, they are often adequate to illustrate the broader patterns of life's history.[22] There are also biases in the fossil record: different environments are more favourable to the preservation of different types of organism or parts of organisms.[23] Further, only the parts of organisms that were already mineralised are usually preserved, such as the shells of molluscs. Since most animal species are soft-bodied, they decay before they can become fossilised. As a result, although there are 30-plus phyla of living animals, two-thirds have never been found as fossils.[10]

.png)

The Cambrian fossil record includes an unusually high number of lagerstätten, which preserve soft tissues. These allow palæontologists to examine the internal anatomy of animals which in other sediments are only represented by shells, spines, claws, etc – if they are preserved at all. The most significant Cambrian lagerstätten are the early Cambrian Maotianshan shale beds of Chengjiang (Yunnan, China) and Sirius Passet (Greenland);[24] the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale (British Columbia, Canada);[25] and the late Cambrian Orsten (Sweden) fossil beds.

While lagerstätten preserve far more than the conventional fossil record, they are far from complete. Because lagerstätten are restricted to a narrow range of environments (where soft-bodied organisms can be preserved very quickly, e.g. by mudslides), most animals are probably not represented; further, the exceptional conditions that create lagerstätten probably do not represent normal living conditions.[26] In addition, the known Cambrian lagerstätten are rare and difficult to date, while Precambrian lagerstätten have yet to be studied in detail.

The sparseness of the fossil record means that organisms usually exist long before they are found in the fossil record – this is known as the Signor-Lipps effect.[27]

Trace fossils

Trace fossils consist mainly of tracks and burrows, but also include coprolites (fossil feces) and marks left by feeding.[28][29] Trace fossils are particularly significant because they represent a data source that is not limited to animals with easily-fossilized hard parts, and which reflects organisms' behaviour. Also many traces date from significantly earlier than the body fossils of animals that are thought to have been capable of making them.[30] Whilst exact assignment of trace fossils to their makers is generally impossible, traces may for example provide the earliest physical evidence of the appearance of moderately complex animals (comparable to earthworms).[29]

Geochemical observations

Several chemical markers indicate a drastic change in the environment around the start of the Cambrian. The markers are consistent with a mass extinction,[31][32] or with a massive warming resulting from the release of methane ice. [19] Such changes may reflect a cause of the Cambrian explosion, although they may also have resulted from an increased level of biological activity – a possible result of the explosion.[19] Despite these uncertainties, the geochemical evidence helps by making scientists focus on theories that are consistent with at least one of the likely environmental changes.

Phylogenetic techniques

Cladistics is a technique for working out the “family tree” of a set of organisms. It works by the logic that, if groups B and C have more similarities to each other than either has to group A, then B and C are more closely related to each other than either is to A. Characteristics which are compared may be anatomical, such as the presence of a notochord, or molecular, by comparing sequences of DNA or protein. The result of a successful analysis is a hierarchy of clades – groups whose members are believed to share a common ancestor. The cladistic technique is sometimes fallible, as some features, such as wings or camera eyes, evolved more than once, convergently – this must be taken into account in analyses.

From the relationships, it may be possible to constrain the date that lineages first appeared. For instance, if fossils of B or C date to X million years ago and the calculated "family tree" says A was an ancestor of B and C, then A must have evolved more than X million years ago.

It is also possible to estimate how long ago two living clades diverged – i.e. approximately how long ago their last common ancestor must have lived – by assuming that DNA mutations accumulate at a constant rate. These "molecular clocks", however, are fallible, and provide only a very approximate timing: they are not sufficiently precise and reliable for estimating when the groups that feature in the Cambrian explosion first evolved,[33] and estimates produced by different techniques vary by a factor of two.[34] However, the clocks can give an indication of branching rate, and when combined with the constraints of the fossil record, recent clocks suggest a sustained period of diversification through the Ediacaran and Cambrian.[35]

Explanation of a few scientific terms

descent

A phylum is the highest level in the Linnean system for classifying organisms. Phyla can be thought of as groupings of animals based on general body plan.[37] Despite the seemingly different external appearances of organisms, they are classified into phyla based on their internal and developmental organizations.[38] For example, despite their obvious differences, spiders and barnacles both belong to the phylum Arthropoda; but earthworms and tapeworms, although similar in shape, belong to different phyla.

A phylum is not a fundamental division of nature, such as the difference between electrons and protons. It is simply a very high-level grouping in a classification system created to describe all currently living organisms. This system is imperfect, even for modern animals: different books quote different numbers of phyla, mainly because they disagree about the classification of a huge number of worm-like species. As it is based on living organisms, it accommodates extinct organisms poorly, if at all.[10][39]

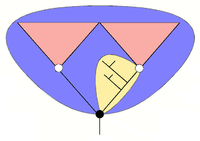

The concept of stem groups was introduced to cover evolutionary "aunts" and "cousins" of living groups. A crown group is a group of closely-related living animals plus their last common ancestor plus all its descendants. A stem group is a set of offshoots from the lineage at a point earlier than the last common ancestor of the crown group; it is a relative concept, for example tardigrades are living animals which form a crown group in their own right, but Budd (1996) regarded them also as being a stem group relative to the arthropods.[36][40]

Triploblastic means consisting of 3 layers, which are formed in the embryo, quite early in the animal's development from a single-celled egg to a larva or juvenile form. The innermost layer forms the digestive tract (gut); the outermost forms skin; and the middle one forms muscles and all the internal organs except the digestive system. Most types of living animal are triploblastic – the best-known exceptions are Porifera (sponges) and Cnidaria (jellyfish, sea anemones, etc.).

The bilaterians are animals which have right and left sides at some point in their life history. This implies that they have top and bottom surfaces and, importantly, distinct front and back ends. All known bilaterian animals are triploblastic, and all known triploblastic animals are bilaterian. Living Echinoderms (sea stars, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, etc.) look radially symmetrical (like wheels) rather than bilaterian, but their larvae exhibit bilateral symmetry and some of the earliest echinoderms may have been bilaterally symmetrical.[41] Porifera and Cnidaria are radially symmetrical, non-bilaterian and non-triploblastic.

Coelomate means having a body cavity (coelom) which contains the internal organs. Most of the phyla featured in the debate about the Cambrian explosion are coelomates: arthropods, annelid worms, molluscs, echinoderms and chordates – the non-coelomate priapulids are an important exception. All known coelomate animals are triploblastic bilaterians, but some triploblastic bilaterian animals do not have a coelom – for example flatworms, whose organs are surrounded by unspecialized tissues.

Precambrian life

Our understanding of the Cambrian explosion relies upon knowing what was there beforehand – did the event herald the sudden appearance of a wide range of animals and behaviours, or did such things exist beforehand?

Evidence of animals around 1 billion years ago

- For further information, see Acritarch and Stromatolite

Changes in the abundance and diversity of some types of fossil have been interpreted as evidence for "attacks" by animals or other organisms. Stromatolites, stubby pillars built by colonies of microorganisms, are a major constituent of the fossil record from about 2,700 million years ago, but their abundance and diversity declined steeply after about 1,250 million years ago. This decline has been attributed to disruption by grazing and burrowing animals.[16][17][42]

Precambrian marine diversity was dominated by small fossils known as acritarchs. This term describes almost any small organic walled fossil–from the egg cases of small metazoans to resting cysts of many different kinds of green algae. After appearing around 2,000 million years ago, acritarchs underwent a boom around 1,000 million years ago, increasing in abundance, diversity, size, complexity of shape and especially size and number of spines. Their increasingly spiny forms in the last 1 billion years may indicate an increased need for defence against predation. Other groups of small organisms from the Neoproterozoic era also show signs of anti-predator defenses.[42] A consideration of taxon longevity appears to support an increase in predation pressure around this time,[43] However, in general, the rate of evolution in the Precambrian was very slow, with many cyanobacterial species persisting unchanged for billions of years.[4]

If these predatory organisms really were metazoans, this means that Cambrian animals did not appear "from no-where" at the base of the Cambrian; their predecessors had existed for hundreds of millions of years.

Fossils of the Doushantuo formation

The 580 million year old[44] Doushantuo formation harbours microscopic fossils which may represent early bilaterians. Some have been described as animal embryos and eggs, although some of these may represent the remains of giant bacteria.[45] Another fossil, Vernanimalcula, has been interpreted as a coelomate bilaterian,[46] but may simply be an infilled bubble.[47]

These fossils form the earliest hard-and-fast evidence of animals, as opposed to other predators.[45][48]

Burrows

The traces of organisms moving on and directly underneath the microbial mats that covered the Ediacaran sea floor are preserved from the Ediacaran period, about 565 million years ago. They were probably made by organisms resembling earthworms in shape, size, and how they moved. The burrow-makers have never been found preserved, but because they would need a head and a tail, the burrowers probably had bilateral symmetry – which would in all probability make them bilaterian animals.[49] They fed above the sediment surface, but were forced to burrow to avoid predators.[50]

Around the start of the Cambrian (about 542 million years ago) many new types of traces first appear, including well-known vertical burrows such as Diplocraterion and Skolithos, and traces normally attributed to arthropods, such as Cruziana and Rusophycus. The vertical burrows indicate that worm-like animals acquired new behaviours, and possibly new physical capabilities. Some Cambrian trace fossils indicate that their makers possessed hard exoskeletons, although there were not necessarily mineralised.[51]

Burrows provide firm evidence of complex organisms; they are also much more readily preserved than body fossils, to the extent that the absence of trace fossils has been used to imply the genuine absence of large, motile bottom-dwelling organisms. They provide a further line of evidence to show that the Cambrian explosion represents a real diversification, and is not a preservational artefact.[52]

Indeed, as burrowing became established, it allowed an explosion of its own, for as burrowers disturbed the sea floor, they aerated it, mixing oxygen into the toxic muds. This made the bottom sediments more hospitable, and allowed a wider range of organisms to inhabit them – creating new niches and the scope for higher diversity.[52]

Ediacaran organisms

At the start of the Ediacaran period, much of the acritarch fauna, which had remained relatively unchanged for hundreds of millions of years, became extinct, to be replaced with a range of new, larger species which would prove far more ephemeral.[4] This radiation, the first in the fossil record,[4] is followed soon after by an array of unfamiliar, large, fossils dubbed the Ediacara biota,[53] which flourished for 40 million years until the start of the Cambrian.[54] Most of this "Ediacara biota" were at least a few centimeters long, significantly larger than any earlier fossils. The organisms form three distinct assemblages, increasing in size and complexity as time progresses.[55]

Many of these organisms were quite unlike anything that appeared before or since, resembling discs, mud-filled bags, or quilted mattresses – one palæontologist proposed that the strangest organisms should be classified as a separate kingdom, Vendozoa.[56]

At least some may have been early forms of the phyla at the heart of the "Cambrian explosion" debate, having been interpreted as early molluscs (Kimberella),[18][57] echinoderms (Arkarua);[58] and arthropods (Spriggina,[59] Parvancorina[60]). There is still debate about the classification of these specimens, mainly because the diagnostic features which allow taxonomists to classify more recent organisms, such as similarities to living organisms, are generally absent in the Ediacarans.[61] However there seems little doubt that Kimberella was at least a triploblastic bilaterian animal.[61] These organisms are central to the debate about how abrupt the Cambrian explosion was. If some were early members of the animal phyla seen today, the "explosion" looks a lot less sudden than if all these organisms represent an unrelated "experiment", and were replaced by the animal kingdom fairly soon thereafter (40M years is "soon" by evolutionary and geological standards).

Ediacaran–Early Cambrian skeletalization

The first Ediacaran and lowest Cambrian (Nemakit-Daldynian) skeletal fossils represent tubes and problematic sponge spicules. The oldest sponge spicules are monaxon siliceous, aged around 580 million years ago, known from the Doushantou Formation in the China and from deposits of the same age in Mongolia. In the late Ediacaran-lowest Cambrian, numerous tube dwellings of enigmatic organisms appeared. It was organic-walled tubes (e.g. Saarina) and chitinous tubes of the sabelliditids (e.g. Sokoloviina, Sabellidites, Paleolina) [62][63] which prospered up to the beginning of the Tommotian. The mineralized tubes of Cloudina, Namacalathus, Sinotubulites and a dozen more of the other organisms from carbonate rocks formed near the end of the Ediacaran period from 549 to 542 million years ago, as well as the triradially symmetrical mineralized tubes of anabaritids (e.g. Anabarites, Cambrotubulus) from uppermost Ediacaran and lower Cambrian.[64] It is interesting to notice that Ediacaran mineralized tubes are often found in carbonates of the stromatolite reefs and thrombolites,[65][66] i.e. they could live in environment adverse for the majority of animals.

Although they are as hard to classify as most other Ediacaran organisms, they are important in two other ways. First, they are the earliest known calcifying organisms (organisms that built shells out of calcium carbonate).[67][66][68] Secondly, these tubes are a device to rise over a substrate and competitors for effective feeding and, to a lesser degree, they serve as armor for protection against predators and adverse conditions of environment. Some Cloudina fossils show small holes in shells. It is possible that the holes are evidence of boring by predators sufficiently advanced to penetrate shells.[69] A possible "evolutionary arms race" between predators and prey is one of the theories that attempt to explain the Cambrian explosion.[42]

In the lowest Cambrian occurs the extinction of stromatolites. This allowed animals to begin colonization of warm-water pools with carbonate sedimentation. At first it was anabaritids and Protohertzina (the fossilized grasping spines of chaetognaths) fossils. Such mineral skeletons as shells, sclerites, thorns and plates appeared in uppermost Nemakit-Daldynian; they were the earliest species of halkierids, gastropods, hyoliths and other rare organisms. The beginning of the Tommotian is characterized by an explosive increase of the number and variety of fossils of mollusks, hyoliths and sponges. At this time appeared a rich complex of skeletal elements of unknown animals, the first archaeocyathids, brachiopods, tommotiids and others.[70][71][72][73]

Some animals may already have had sclerites, thorns and plates in the Ediacaran (e.g. Kimberella had hard sclerites, probably of carbonate), but thin carbonate skeletons cannot be fossilized in siliciclastic deposits.[74]

Cambrian life

Small shelly fauna

Fossils known as “small shelly fauna” have been found in many parts on the world, and date from just before the Cambrian to about 10 million years after the start of the Cambrian (the Nemakit-Daldynian and Tommotian ages; see timeline). These are a very mixed collection of fossils: spines, sclerites (armor plates), tubes, archeocyathids (sponge-like animals) and small shells very like those of brachiopods and snail-like molluscs – but all tiny, mostly 1 to 2 mm long.[75]

While small, these fossils are far more common than complete fossils of the organisms that produced them; crucially, they cover the window from the start of the Cambrian to the first lagerstatten: a period of time that is otherwise lacking in fossils. Hence they supplement the conventional fossil record, and allow the fossil ranges of many groups to be extended.

Early Cambrian trilobites and echinoderms

The earliest Cambrian trilobite fossils are about 530 million years old, but the class was already quite diverse and worldwide, suggesting that they had been around for quite some time.[76] It is important to remember that the fossil record of trilobites begins from the time of appearance of trilobites with mineral exoskeleton - not from the time of their origin.

The earliest generally-accepted echinoderm fossils appeared a little bit later, in the Late Atdabanian; unlike modern echinoderms, these early Cambrian echinoderms were not all radially symmetrical.[77]

These provide firm data points for the "end" of the explosion, or at least indications that the crown groups of modern phyla were represented.

Burgess shale type faunas

The Burgess shale and similar lagerstatten preserve the soft parts of organisms, which provides a wealth of data to aid in the classification of enigmatic fossils. It often preserved complete specimens of organisms only otherwise known from dispersed parts, such as loose scales or isolated mouthparts. Further, the majority of organisms and taxa in these horizons are entirely soft bodied – hence absent from the rest of the fossil record.[78] Since a large part of the ecosystem is preserved, the ecology of the community can also be tentatively reconstructed. However, the assemblages may represent a "museum": a deep water ecosystem that is evolutionarily "behind" the rapidly diversifying faunas of shallower waters.[79]

Because the lagerstatten provide a mode and quality of preservation that's virtually absent outside of the Cambrian, lots of organisms appear completely different to anything known from the conventional fossil record. This led early workers in the field to attempt to shoehorn the organisms into extant phyla; the shortcomings of this approach led them to erect a multitude of new phyla to accommodate all the oddballs. It has since been realised that most oddballs diverged from lineages before they established the phyla we know today – slightly different designs, which were fated to perish rather than flourish into phyla, as their cousin lineages did.

The preservational mode is rare in the preceding Ediacaran period, but those assemblages known show no trace of animal life – perhaps implying a genuine absence of macroscopic metazoans.[80]

Early Cambrian crustaceans

Crustaceans, one of the four great modern groups of arthropods, are very rare throughout the Cambrian. Convincing crustaceans were once thought to be common in Burgess shale-type biotas, but none of these individuals can be shown to fall into the crown group of "true crustaceans".[81] The Cambrian record of crown group crustaceans comes from microfossils. The Swedish Orsten horizons contain later Cambrian crustacea, but only organisms smaller than 2 mm are preserved. This restricts the data set to juveniles and miniaturised adults.

A more informative data source is the organic microfossils of the Mount Cap formation, Canada. This late Early Cambrian assemblage (510 to 515 million years ago) consists of microscopic fragments of arthropods' cuticle, which is left behind when the rock is dissolved with a strong acid. The diversity of this assemblage is similar to that of modern crustacean faunas. Most interestingly, analysis of fragments of feeding machinery found in the formation shows that it was adapted to feed in a very precise and refined fashion. This contrasts with most other early Cambrian arthropods, which fed messily by shovelling anything they could get their feeding appendages on into their mouths. This sophisticated and specialised feeding machinery belonged to a large (~30 cm)[82] organism, and would have provided great potential for diversification: specialised feeding apparatus allows a number of different approaches to feeding and development, and creates a number of different approaches to avoid being eaten[81]

Early Ordovician radiation

After a mass extinction at the Cambrian-Ordovician boundary, another radiation occurred, which established the taxa which would dominate the Palaeozoic.[83]

During this radiation, the total number of orders doubled, and families tripled,[83] increasing marine diversity to levels typical of the Palaeozoic,[19] and disparity to levels approximately equivalent to today's.[5]

How real was the explosion?

The fossil record as Darwin knew it seemed to suggest that the major metazoan groups appeared in a few million years of the early to mid-Cambrian, and even in the 1980s this still appeared to be the case.[13][14]

However, evidence of Precambrian metazoa is gradually accumulating. If the Ediacaran Kimberella was a mollusc-like protostome (one of the two main groups of coelomates),[18][57] the protostome and deuterostome lineages must have split significantly before 550 million years ago (deuterostomes are the other main group of coelomates).[84] Even if it is not a protostome, it is widely accepted as a bilaterian.[61][84] Since fossils of rather modern-looking Cnidarians (jellyfish-like organisms) have been found in the Doushantuo lagerstätte, the Cnidarian and bilaterian lineages must have diverged well over 580 million years ago.[84]

Trace fossils[55] and predatory borings in Cloudina shells provide further evidence of Ediacaran animals.[85] Some fossils from the Doushantuo formation have been interpreted as embryos and one (Vernanimalcula) as a bilaterian coelomate, although these interpretations are not universally accepted.[46][47][86] Earlier still, predatory pressure has acted on stromatolites and acritarchs since around 1,250 million years ago.[42]

The presence of Precambrian animals somewhat dampens the "bang" of the explosion: not only was the appearance of animals gradual, but their evolutionary radiation ("diversification") may also not have been as rapid as once thought. Indeed, statistical analysis shows that the Cambrian explosion was no faster than any of the other radiations in animals' history.[4] However, it does seem that some innovations linked to the explosion — such as resistant armour — only evolved once in the animal lineage; this makes a lengthy Precambrian animal lineage harder to defend.[87]

There is little doubt that disparity – that is, the range of different organism "designs" or "ways of life" – rose sharply in the early Cambrian.[5] However, recent research has overthrown the once-popular idea that disparity was exceptionally high throughout the Cambrian, before subsequently decreasing.[88] In fact, disparity remains relatively low throughout the Cambrian, with modern levels of disparity only attained after the early Ordovician radiation.[5]

The diversity of many Cambrian assemblages is similar to today's.[89][81]

Possible causes of the “explosion”

Despite the evidence that moderately complex animals (triploblastic bilaterians) existed before and possibly long before the start of the Cambrian, it seems that the pace of evolution was exceptionally fast in the early Cambrian. Possible explanations for this fall into three broad categories: environmental, developmental, and ecological changes. Any explanation must explain the timing and magnitude of the explosion. It is also possible that the "explosion" requires no special explanation.

Changes in the environment

Increase in oxygen levels

Earth’s earliest atmosphere contained no free oxygen; the oxygen that animals breathe today, both in the air and dissolved in water, is the product of billions of years of photosynthesis. As a general trend, the concentration of oxygen in the atmosphere has risen gradually over about the last 2.5 billion years.[10]

Shortage of oxygen might well have prevented the rise of large, complex animals. The amount of oxygen an animal can absorb is largely determined by the area of its oxygen-absorbing surfaces (lungs and gills in the most complex animals; the skin in less complex ones); but the amount needed is determined by its volume, which grows faster than the oxygen-absorbing area if an animal’s size increases equally in all directions. An increase in the concentration of oxygen in air or water would increase the size to which an organism could grow without its tissues becoming starved of oxygen. However, members of the Ediacara biota reached metres in length; clearly oxygen did not limit their growth.[31] Other metabolic functions may have been inhibited by lack of oxygen, for example the construction of tissue such as collagen, required for the construction of complex structures,[90] or to form molecules for the construction of a hard exoskeleton.[91] However, animals are not affected when similar oceanographic conditions occur in the Phanerzoic; there is no convincing correlation between oxygen levels and evolution, so oxygen may have been no more a prerequisite to complex life than liquid water or primary productivity.[92]

Snowball Earths

In the late Neoproterozoic (extending into the early Ediacaran period), the Earth suffered massive glaciations in which most of its surface was covered by ice. This may have caused a mass extinction, creating a genetic bottleneck; the resulting diversification may have given rise to the Ediacara biota, which appears soon after the last "Snowball Earth" episode.[93] However, the snowball episodes occurred a long time before the start of the Cambrian, and it is hard to see how so much diversity could have been caused by even a series of bottlenecks;[19] the cold periods may even have delayed the evolution of large size.[42]

Developmental explanations

A range of theories are based on the concept that minor modifications to animals' development as they grow from embryo to adult may have been able to cause very large changes in the final adult form. The hox genes, for example, control which organs individual regions of an embryo will develop into. For instance, if a certain hox gene is expressed, a region will develop into a limb; if a different hox gene is expressed in that region (a minor change), it could develop into an eye instead (a phenotypically major change).

Such a system allows a large range of disparity to appear from a limited set of genes, but such theories linking this with the explosion struggle to explain why the origin of such a development system should by itself lead to increased diversity or disparity. Evidence of Precambrian metazoans[19] combines with molecular data[94] to show that much of the genetic architecture that could feasibly have played a role in the explosion was already well established by the Cambrian.

This apparent paradox is addressed in a theory that focuses on the physics of development. It is proposed that the emergence of simple multicellular forms provided a changed context and spatial scale in which novel physical processes and effects were mobilized by the products of genes that had previously evolved to serve unicellular functions. Morphological complexity (layers, segments, lumens, appendages) arose, in this view, by self-organization.[95]

Ecological explanations

These focus on the interactions between different types of organism. Some of these hypotheses deal with changes in the food chain; some suggest arms races between predators and prey, and others focus on the more general mechanisms of coevolution. Such theories are well suited to explaining why there was a rapid increase in both disparity and diversity, but they must explain why the "explosion" happened when it did.[19]

End-Ediacaran mass extinction

Evidence for such an extinction includes the disappearance from the fossil record of the Ediacara biota and shelly fossils such as Cloudina, and the accompanying perturbation in the δ13C record. Mass extinctions are often followed by adaptive radiations as existing clades expand to occupy the ecospace emptied by the extinction. However, once the dust had settled, overall disparity and diversity returned to the pre-extinction level in each of the Phanerozoic extinctions.[19]

Evolution of eyes

Andrew Parker has proposed that predator-prey relationships changed dramatically after eyesight evolved. Prior to that time hunting and evading were both close-range affairs – smell, vibration, and touch were the only senses used. When predators could see their prey from a distance, new defensive strategies were needed. Armor, spines, and similar defenses may also have evolved in response to vision. He further observed that where animals lose vision in unlighted environments such as caves, diversity of animal forms tends to decrease.[96] Nevertheless many scientists doubt that vision could have caused the explosion. Eyes may well have evolved long before the start of the Cambrian.[97] It is also difficult to understand why the evolution of eyesight would have caused an explosion, since other senses such as smell and pressure detection can detect things further away than they can be seen under the sea, but the appearance of these other senses apparently did not cause an evolutionary explosion.[19]

Arms races between predators and prey

The ability to avoid or recover from predation often makes the difference between life and death, and is therefore one of the strongest components of natural selection. The pressure to adapt is stronger on the prey than on the predator: if the predator fails to win a contest, it loses its lunch; if the prey is the loser, it loses its life.[98]

But there is evidence that predation was rife long before the start of the Cambrian, for example in the increasingly spiny forms of acritarchs, the holes drilled in Cloudina shells, and traces of burrowing to avoid predators. Hence it is unlikely that the appearance of predation was the trigger for the Cambrian "explosion", although it may well have exhibited a strong influence on the body forms that the "explosion" produced.[42] Alternatively a more subtle aspect, such as the evolution of a new style of predation, may have played a role.

Increase in size and diversity of planktonic animals

Geochemical evidence strongly indicates that the total mass of plankton has been similar to modern levels since early in the Proterozoic. Before the start of the Cambrian, their corpses and droppings were too small to fall quickly towards the seabed, since their drag was about the same as their weight. This meant they were destroyed by scavengers or by chemical processes before they reached the sea floor.[26]

Mesozooplankton are plankton of a larger size, and early Cambrian specimens filtered microscopic plankton from the seawater. These larger organisms would have produced droppings and corpses that were large enough to fall fairly quickly. This provided a new supply of energy and nutrients to the mid-levels and bottoms of the seas, which opened up a huge range of new possible ways of life. If any of these remains sank uneaten to the sea floor they could be buried; this would have taken some carbon out of circulation, resulting in an increase in the concentration of breathable oxygen in the seas (carbon readily combines with oxygen).[26]

The initial herbivorous mesozooplankton were probably larvae of benthic (seafloor) animals. A larval stage was probably an evolutionary innovation driven by the increasing level of predation at the seafloor during the Ediacaran period.[3][99]

Metazoans have an amazing ability to increase diversity through co-evolution.[4] This means that a trait of one organism can cause another to evolve in response; a number of responses are possible, and a different species can potentially emerge for each. As a simple example, the evolution of predation may have caused one organism to develop defence while another developed motion to flee. This would cause the predator lineage to split into two species: one that was good at chasing prey, and another that was good at breaking through defences. Actual co-evolution is somewhat more subtle, but in this fashion, great diversity can arise: three quarters of living species are animals, and most of the rest have formed by co-evolution with animals.[4]

Mis-dating of species

The results of an article published in Nature, in 2010, have shown that the eukaryotic multicellularity which has been thought to evolve with the beginning of Cambrian Period might date back to 2.1 billions of years ago, which is approximately 1.55 billions of years earlier than the date indicated by dominating scientific evidences[100].

Discredited hypotheses

As our understanding of the events of the Cambrian becomes clearer, data has accumulated to make some hypotheses look improbable. Causes that have been proposed but are now discounted include the evolution of herbivory, vast changes in the speed of tectonic plate movement or of the cyclic changes in the Earth's orbital motion, or the operation of different evolutionary mechanisms from those that are seen in the rest of the Phanerozoic eon.

No explanation required

The explosion may not have been a significant evolutionary event. It may represent a threshold being crossed: for example a threshold in genetic complexity that allowed a vast range of morphological forms to be employed.[101]

Uniqueness of the explosion

The "Cambrian explosion" can be viewed as two waves of metazoan expansion into empty niches: first, a co-evolutionary rise in diversity as animals explored niches on the Ediacaran sea floor, followed by a second expansion in the early Cambrian as they became established in the water column.[4] The rate of diversification seen in the Cambrian phase of the explosion is unparalleled among marine animals: it affected all metazoan clades of which Cambrian fossils have been found. Later radiations, such as those of fish in the Silurian and Devonian periods, involved fewer taxa, mainly with very similar body plans.[10] Although the recovery from the Permian-Triassic extinction started with about as few animal species as the Cambrian explosion, the recovery produced far fewer significantly new types of animals.[102]

Whatever triggered the early Cambrian diversification opened up an exceptionally wide range of previously-unavailable ecological niches. When these were all occupied, there was little room for such wide-ranging diversifications to occur again, because there was strong competition in all niches and incumbents usually had the advantage. If there had continued to be a wide range of empty niches, clades would be able to continue diversifying and become disparate enough for us to recognise them as different phyla; when niches are filled, lineages will continue to resemble one another long after they diverge, as there is limited opportunity for them to change their life-styles and forms.[103]

There is a similar one-time explosion in the evolution of land plants: after a cryptic history beginning about 450 million years ago, land plants underwent a uniquely rapid adaptive radiation during the Devonian period, about 400 million years ago.[10]

Further reading

| Part of a series on | |||||||||||

| The Cambrian explosion | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

• taskforce |

- Budd, G. E. & Jensen, J. (2000). "A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla". Biological Reviews 75 (2): 253–295. doi:10.1017/S000632310000548X. PMID 10881389.

- Collins, Allen G. “Metazoa: Fossil record”. Retrieved Dec. 14, 2005.

- Conway Morris, S. (1997). The Crucible of Creation: the Burgess Shale and the rise of animals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0–19–286202–2.

- Conway Morris, S. (June 2006). "Darwin’s dilemma: the realities of the Cambrian ‘explosion’". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 361 (1470): 1069–1083. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1846. ISSN 0962-8436. PMID 16754615. An enjoyable account.

- Gould, S.J. (1989). Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Kennedy, M., M. Droser, L. Mayer., D. Pevear, and D. Mrofka (2006). "Clay and Atmospheric Oxygen". Science 311 (5766): 1341. doi:10.1126/science.311.5766.1341c.

- Knoll, A. H. and Carroll, S. B. (1999). Early Animal Evolution: Emerging Views from Comparative Biology and Geology. Science 284 (5423): 2129 – 2137.

- Alexander V. Markov, and Andrey V. Korotayev (2007) “Phanerozoic marine biodiversity follows a hyperbolic trend” Palaeoworld 16(4): pp. 311–318.

- "MONTENARI, M. & LEPPIG, U. (2003): The Acritarcha: their classification morphology, ultrastructure and palaeoecological/palaeogeographical distribution.". Paläontologische Zeitschrift 77: 173–194. 2003.

- Wang, D. Y.-C., S. Kumar and S. B. Hedges (January 1999). "Divergence time estimates for the early history of animal phyla and the origin of plants, animals and fungi". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences 266 (1415): 163–71. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0617. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 10097391.

- Xiao, S., Y. Zhang, and A. Knoll (January 1998). "Three-dimensional preservation of algae and animal embryos in a Neoproterozoic phosphorite". Nature 391 (1): 553–58. doi:10.1038/35318. ISSN 0090-9556. PMID 35318.

Timeline References:

- Martin, M.W; Grazhdankin, D.V; Bowring, S.A; Evans, D.A.D; Fedonkin, M.A; Kirschvink, J.L (2000). "Age of Neoproterozoic Bilaterian Body and Trace Fossils, White Sea, Russia: Implications for Metazoan Evolution". Science 288 (5467): 841–845. doi:10.1126/science.288.5467.841. PMID 10797002.

Notes

^1 Older marks found in billion-year old rocks[104] have since been recognised as non-biogenic.[51][105]

^2 The analysis considered the bioprovinciality of trilobite lineages, as well as their evolutionary rate.[106]

References

- ↑ The Cambrian Period

- ↑ The Cambrian Explosion – Timing

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Butterfield, N.J. (2001). "Ecology and evolution of Cambrian plankton" (PDF). The Ecology of the Cambrian Radiation. Columbia University Press, New York. pp. 200–216. ISBN 9780231106139. http://books.google.com/?id=oWcepB3Q-rIC&lpg=PR7&dq=%20The%20Ecology%20of%20the%20Cambrian%20Radiation&pg=PR7#v=onepage&q. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00613.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Bambach, R.K.; Bush, A.M., Erwin, D.H. (2007). "Autecology and the filling of Ecospace: Key metazoan radiations". Palæontology 50 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00611.x.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Buckland, W. (1841). Geology and Mineralogy Considered with Reference to Natural Theology. Lea & Blanchard.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Darwin, C (1859). On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection. Murray, London, United Kingdom. pp. 315–316. ISBN 1602061440. OCLC 176630493.

- ↑ Walcott, C.D. (1914). "Cambrian Geology and Paleontology". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 57: 14.

- ↑ Holland, Heinrich D (January 3, 1997). "Evidence for life on earth more than 3850 million years ago". Science 275 (5296): 38. doi:10.1126/science.275.5296.38. PMID 11536783.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Cowen, R. (2002). History of Life. Blackwell Science. ISBN 0931292387. OCLC 53325609.

- ↑ Cloud, P.E. (1948). "Some problems and patterns of evolution exemplified by fossil invertebrates". Evolution 2 (4): 322–350. doi:10.2307/2405523. PMID 18122310. http://www.jstor.org/pss/2405523. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ Whittington, H. B. (1979). Early arthropods, their appendages and relationships. In M. R. House (Ed.), The origin of major invertebrate groups (pp. 253–268). The Systematics Association Special Volume, 12. London: Academic Press.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Whittington, H.B.; Geological Survey of Canada (1985). The Burgess Shale. Yale University Press. ISBN 0660119013. OCLC 15630217.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Gould, S.J. (1989). Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393027058. OCLC 185746546.

- ↑ Bengtson, S. (2004). Early skeletal fossils. In Lipps, J.H., and Waggoner, B.M.. "Neoproterozoic- Cambrian Biological Revolutions" (PDF). Palentological Society Papers 10: 67–78. http://www.nrm.se/download/18.4e32c81078a8d9249800021554/Bengtson2004ESF.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 McNamara, K.J. (20 December 1996). "Dating the Origin of Animals". Science 274 (5295): 1993–1997. doi:10.1126/science.274.5295.1993f.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Awramik, S.M. (19 November 1971). "Precambrian columnar stromatolite diversity: Reflection of metazoan appearance". Science 174 (4011): 825–827. doi:10.1126/science.174.4011.825. PMID 17759393.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Fedonkin, M. A.; Waggoner, B. (November 1997). "The late Precambrian fossil Kimberella is a mollusc-like bilaterian organism" (abstract). Nature 388 (11): 868–871. doi:10.1038/42242. ISSN 0372-9311. PMID 42242. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v388/n6645/abs/388868a0.html.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 19.8 Marshall, C.R. (2006). "Explaining the Cambrian “Explosion” of Animals" (abstract). Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 34: 355–384. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.33.031504.103001. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.earth.33.031504.103001?journalCode=earth.

- ↑ e.g. Jago, J.B.; Haines, P.W. (1998). "Recent radiometric dating of some Cambrian rocks in southern Australia: relevance to the Cambrian time scale". Revista Española de Paleontología: 115–22.

- ↑ e.g. Gehling, James; Jensen, Sören; Droser, Mary; Myrow, Paul; Narbonne, Guy (March 2001). "Burrowing below the basal Cambrian GSSP, Fortune Head, Newfoundland". Geological Magazine 138 (2): 213–218. doi:10.1017/S001675680100509X. http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=74669.

- ↑ Benton MJ, Wills MA, Hitchin R (2000). "Quality of the fossil record through time". Nature 403 (6769): 534–7. doi:10.1038/35000558. PMID 10676959.

- Non-technical summary

- ↑ Butterfield , N.J. (2003). "Exceptional Fossil Preservation and the Cambrian Explosion". Integrative and Comparative Biology 43 (1): 166–177. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.166. http://icb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/43/1/166. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ↑ Morris, S.C. (1979). "The Burgess Shale (Middle Cambrian) Fauna". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 10 (1): 327–349. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.10.110179.001551.

- ↑ Yochelson, E.L. (1996). "Discovery, Collection, and Description of the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale Biota by Charles Doolittle Walcott". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 140 (4): 469–545. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003–049X(199612)140%3A4%3C469%3ADCADOT%3E2.0.CO%3B2–8. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Butterfield, N.J. (2001). "Ecology and evolution of Cambrian plankton". The Ecology of the Cambrian Radiation. Columbia University Press, New York: 200–216. ISBN 9780231106139. http://books.google.com/?id=lbZUxpj4i6UC&lpg=PA200&dq=%20Ecology%20and%20evolution%20of%20Cambrian%20plankton&pg=PA200#v=onepage&q=Ecology%20and%20evolution%20of%20Cambrian%20plankton. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ↑ Signor, P.W. (1982). "Sampling bias, gradual extinction patterns and catastrophes in the fossil record". Geological implications of impacts of large asteroids and comets on the earth (Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America): 291–296. A 84–25651 10–42. http://www.csa.com/partners/viewrecord.php?requester=gs&collection=TRD&recid=A8425675AH. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ "What is paleontology?". University of California Museum of Paleontology. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/faq.php#paleo. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Fedonkin, M.A., Gehling, J.G., Grey, K., Narbonne, G.M., Vickers-Rich, P. (2007). The Rise of Animals: Evolution and Diversification of the Kingdom Animalia. JHU Press. pp. 213–216. ISBN 0801886791. http://books.google.com/?id=OFKG6SmPNuUC&pg=PA213&lpg=PA213&dq=trace+fossil+complex+animal. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ↑ e.g. Seilacher, A. (1994). "How valid is Cruziana Stratigraphy?" (PDF). International Journal of Earth Sciences 83 (4): 752–758. http://www.springerlink.com/content/wp279834395100kh/. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 e.g. Knoll, A.H.; Carroll, S.B. (1999-06-25). "Early Animal Evolution: Emerging Views from Comparative Biology and Geology". Science 284 (5423): 2129. doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2129. PMID 10381872.

- ↑ Amthor, J.E.; Grotzinger, J.P., Schroder, S., Bowring, S.A., Ramezani, J., Martin, M.W., Matter, A. (2003). "Extinction of Cloudina and Namacalathus at the Precambrian-Cambrian boundary in Oman". Geology 31 (5): 431–434. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0431:EOCANA>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Hug, L.A., and Roger, A.J. (August 2007). "The Impact of Fossils and Taxon Sampling on Ancient Molecular Dating Analyses" (Free full text). Molecular Biology and Evolution 24 (8): 889–1897. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm115. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 17556757. http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/24/8/1889?view=long&pmid=17556757.

- ↑ Peterson, Kevin J., and Butterfield, N.J. (2005). "Origin of the Eumetazoa: Testing ecological predictions of molecular clocks against the Proterozoic fossil record". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102 (27): 9547. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503660102. PMID 15983372.

- ↑ Peterson, Kevin J.; Cotton, JA; Gehling, JG; Pisani, D (April 2008). "The Ediacaran emergence of bilaterians: congruence between the genetic and the geological fossil records" (Free full text). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 363 (1496): 1435. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2233. ISSN 0962-8436. PMID 18192191. PMC 2614224. http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/363/1496/1435.long.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Craske, A.J., and Jefferies, R.P.S. (1989). "A new mitrate from the Upper Ordovician of Norway, and a new approach to subdividing a plesion". Palaeontology 32: 69–99.

- ↑ Valentine, James W. (2004). On the Origin of Phyla. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press. p. 7. ISBN 0226845486."Classifications of organisms in hierarchical systems were in use by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. usually organisms were grouped according to their morphological similarities as perceived by those early workers, and those groups were then grouped according to their similarities, and so on, to form a hierarchy."

- ↑ Parker, Andrew (2003). In the blink of an eye: How vision kick-started the big bang of evolution. Sydney: Free Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 0743257332."The job of an evolutionary biologist is to make sense of the conflicting diversity of form – there is not always a relationship between internal and external parts. Early in the history of the subject, it became obvious that internal organisations were generally more important to the higher classification of animals than are external shapes. The internal organisation puts general restrictions on how an animal can exchange gases, obtain nutrients and reproduce."

- ↑ Jefferies, R.P.S. (1979). House, M.R.,. ed. The origin of chordates — a methodological essay. London: Academic Press. pp. 443–477. summarised in Budd, G.E. (2003). "The Cambrian Fossil Record and the Origin of the Phyla". Integrative and Comparative Biology 43 (1): 157–165. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.157. http://icb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/43/1/157.

- ↑ Budd, G.E. (1996). "The morphology of Opabinia regalis and the reconstruction of the arthropod stem-group". Lethaia 29 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1996.tb01831.x.

- ↑ Dominguez, P., Jacobson, A.G., Jefferies, R.P.S. (June 2002). "Paired gill slits in a fossil with a calcite skeleton". Nature 417 (6891): 841–844. doi:10.1038/nature00805. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12075349. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v417/n6891/abs/nature00805.html.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 Bengtson, S. (2002). "Origins and early evolution of predation". In Kowalewski, M., and Kelley, P.H. (Free full text). The fossil record of predation. The Paleontological Society Papers 8. The Paleontological Society. pp. 289– 317. http://www.nrm.se/download/18.4e32c81078a8d9249800021552/Bengtson2002predation.pdf. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ↑ Stanley (2008). "Predation defeats competition on the seafloor" (extract). Paleobiology 34: 1. doi:10.1666/07026.1. http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/extract/34/1/1.

- ↑ Condon, D., Zhu, M., Bowring, S., Wang, W., Yang, A., and Jin, Y. (1 April 2005). "U-Pb Ages from the Neoproterozoic Doushantuo Formation, China" (abstract). Science 308 (5718): 95–98. doi:10.1126/science.1107765. PMID 15731406. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/308/5718/95.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Xiao, S., Zhang, Y. & Knoll, A. H. (January 1998). "Three-dimensional preservation of algae and animal embryos in a Neoproterozoic phosphorite". Nature 391 (1): 553–558. doi:10.1038/35318. ISSN 0090-9556. PMID 35318.

- Hagadorn, J. W.; Xiao, S; Donoghue, PC; Bengtson, S; Gostling, NJ; Pawlowska, M; Raff, EC; Raff, RA et al. (October 2006). "Cellular and Subcellular Structure of Neoproterozoic Animal Embryos". Science 314 (5797): 291–294. doi:10.1126/science.1133129. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17038620.

- Bailey, Jake V.; Joye, SB; Kalanetra, KM; Flood, BE; Corsetti, FA (January 2007). "Evidence of giant sulphur bacteria in Neoproterozoic phosphorites". Nature 445 (7124): 198–201. doi:10.1038/nature05457. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17183268.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Chen, J.Y.; Bottjer, D.J.; Oliveri, P.; Dornbos, S.Q.; Gao, F.; Ruffins, S.; Chi, H.; Li, C.W.; Davidson, E.H. (2004-07-09). "Small Bilaterian Fossils from 40 to 55 Million Years Before the Cambrian". Science 305 (5681): 218–222. doi:10.1126/science.1099213. PMID 15178752.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Bengtson, S.; Budd, G. (2004). "Comment on ‘‘Small bilaterian fossils from 40 to 55 million years before the Cambrian’’". Science 306 (5700): 1291a. doi:10.1126/science.1101338. PMID 15550644.

- ↑ Philip, C. J; Neil, J; John, A (August 2006). "Synchrotron X-ray tomographic microscopy of fossil embryos". Nature 442 (7103): 680. doi:10.1038/nature04890. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16900198.

- ↑ Fedonkin, M.A. (1992). "Vendian faunas and the early evolution of Metazoa". In Lipps, J., and Signor, P. W.. Origin and early evolution of the Metazoa. New York: Springer. pp. 87–129. ISBN 0306440679. OCLC 231467647. http://books.google.com/?id=gUQMKiJOj64C&pg=PP1. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

- ↑ Dzik, J (2007), "The Verdun Syndrome: simultaneous origin of protective armour and infaunal shelters at the Precambrian–Cambrian transition", in Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Komarower, Patricia, The Rise and Fall of the Ediacaran Biota, Special publications, 286, London: Geological Society, pp. 405–414, doi:10.1144/SP286.30, ISBN 9781862392335, OCLC 191881597 156823511 191881597

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Jensen, S. (2003). "The Proterozoic and Earliest Cambrian Trace Fossil Record; Patterns, Problems and Perspectives". Integrative and Comparative Biology 43: 219. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.219.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Seilacher, Adolf; Luis A. Buatoisb, M. Gabriela Mángano (2005-10-07). "Trace fossils in the Ediacaran–Cambrian transition: Behavioral diversification, ecological turnover and environmental shift". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 227 (4): 323–356. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.06.003.

- ↑ Shen, B., Dong, L., Xiao, S. and Kowalewski, M. (January 2008). "The Avalon Explosion: Evolution of Ediacara Morphospace" (abstract). Science 319 (5859): 81–84. doi:10.1126/science.1150279. PMID 18174439. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/319/5859/81.

- ↑ Grazhdankin (2004). "Patterns of distribution in the Ediacaran biotas: facies versus biogeography and evolution". Paleobiology 30: 203. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0203:PODITE>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Erwin, D.H. (June 1999). "The origin of bodyplans" (free full text). American Zoologist 39 (3): 617–629. doi:10.1093/icb/39.3.617. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3746/is_199906/ai_n8843690/.

- ↑ Seilacher, A. (1992). "Vendobionta and Psammocorallia: lost constructions of Precambrian evolution" (abstract). Journal of the Geological Society, London 149 (4): 607–613. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.149.4.0607. http://jgs.lyellcollection.org/cgi/content/abstract/149/4/607. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Martin, M.W.; Grazhdankin, D.V.; Bowring, S.A.; Evans, D.A.D.; Fedonkin, M.A.; Kirschvink, J.L. (2000-05-05). "Age of Neoproterozoic Bilaterian Body and Trace Fossils, White Sea, Russia: Implications for Metazoan Evolution" (abstract). Science 288 (5467): 841. doi:10.1126/science.288.5467.841. PMID 10797002. http://www.scienceonline.org/cgi/content/abstract/288/5467/841. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Mooi, R. and Bruno, D. (1999). "Evolution within a bizarre phylum: Homologies of the first echinoderms" (PDF). American Zoologist 38: 965–974. http://icb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/38/6/965.pdf.

- ↑ McMenamin, M.A.S (2003). "Spriggina is a trilobitoid ecdysozoan" (abstract). Abstracts with Programs (Geological Society of America) 35 (6): 105. http://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2003AM/finalprogram/abstract_62056.htm.

- ↑ doi:10.1080/08912960500508689

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Butterfield, N.J. (December 2006). "Hooking some stem-group "worms": fossil lophotrochozoans in the Burgess Shale". Bioessays 28 (12): 1161–6. doi:10.1002/bies.20507. ISSN 0265-9247. PMID 17120226.

- ↑ Gnilovskaya, M. B. (1996). "New saarinids from the Vendian of the Russian Platform". Dokl. Ross. Akad. Nauk 348: 89–93.

- ↑ Fedonkin, M. A. (2003). "The origin of the Metazoa in the light of the Proterozoic fossil record" (PDF). Paleontological Research 7 (1): 9–41. doi:10.2517/prpsj.7.9. http://www.vend.paleo.ru/pub/Fedonkin_2003.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- ↑ Andrey Yu. Zhuravlev; et al. (September 2009). "First finds of problematic Ediacaran fossil Gaojiashania in Siberia and its origin". Geological Magazine 146 (5): 775–780. doi:10.1017/S0016756809990185. http://geolmag.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/146/5/775.

- ↑ Hofmann, H.J.; Mountjoy, E.W. (2001). "Namacalathus-Cloudina assemblage in Neoproterozoic Miette Group (Byng Formation), British Columbia: Canada's oldest shelly fossils". Geology 29 (12): 1091–1094. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<1091:NCAINM>2.0.CO;2. http://geology.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/29/12/1091.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Grotzinger, J.P.; Watters, W.A., Knoll, A.H. (2000). "Calcified metazoans in thrombolite-stromatolite reefs of the terminal Proterozoic Nama Group, Namibia". Paleobiology 26 (3): 334–359. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0334:CMITSR>2.0.CO;2. http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/26/3/334.

- ↑ Hua, H.; Chen, Z., Yuan, X., Zhang, L., Xiao, S. (2005). [ttp://geology.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/33/4/277 "Skeletogenesis and asexual reproduction in the earliest biomineralizing animal Cloudina"]. Geology 33 (4): 277–280. doi:10.1130/G21198.1. ttp://geology.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/33/4/277. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ Miller, A.J. (2004). "A Revised Morphology of Cloudina with Ecological and Phylogenetic Implications" (PDF). http://ajm.pioneeringprojects.org/files/CloudinaPaper_Final.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ Hua, H.; Pratt, B.R., Zhang, L.U.Y.I. (2003). "Borings in Cloudina Shells: Complex Predator-Prey Dynamics in the Terminal Neoproterozoic". PALAIOS 18: 454. doi:10.1669/0883-1351(2003)018<0454:BICSCP>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Michael Steiner, Guoxiang Li, Yi Qian, Maoyan Zhu and Bernd-Dietrich Erdtmann (2007). "Neoproterozoic to early Cambrian small shelly fossil assemblages and a revised biostratigraphic correlation of the Yangtze Platform (China)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 254: 67–99. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.03.046.

- ↑ A.Yu. Rozanov et al. (2008). "To the problem of stage subdivision of the Lower Cambrian". Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 16 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1007/s11506-008-1001-3. http://www.springerlink.com/content/v6785v3x25263l85/.

- ↑ V. V. Khomentovsky and G. A. Karlova (2005). "The Tommotian Stage Base as the Cambrian Lower Boundary in Siberia". Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 13 (1): 21–34. http://www.maikonline.com/maik/showArticle.do?auid=VAE43XYML4.

- ↑ V. V. Khomentovsky and G. A. Karlova (2002). "The Boundary between Nemakit-Daldynian and Tommotian Stages (Vendian-Cambrian Systems) of Siberia". Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 10 (3): 13–34. http://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=11900587.

- ↑ doi:10.1134/S003103010906001X

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Matthews, S.C.; Missarzhevsky, V.V. (1975-06-01). "Small shelly fossils of late Precambrian and early Cambrian age: a review of recent work". Journal of Geological Society 131 (3): 289. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.131.3.0289.

- ↑ Lieberman, BS (March 1, 1999). "Testing the Darwinian Legacy of the Cambrian Radiation Using Trilobite Phylogeny and Biogeography" (abstract). Journal of Paleontology 73 (2): 176. http://jpaleontol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/73/2/176.

- ↑ Dornbos, S.Q. and Bottjer, D.J. (2000). "Evolutionary paleoecology of the earliest echinoderms: Helicoplacoids and the Cambrian substrate revolution". Geology 28 (9): 839–842. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2000)28<839:EPOTEE>2.0.CO;2. http://geology.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/full/28/9/839.

- ↑ Butterfield, Nicholas J. (2003). "Exceptional Fossil Preservation and the Cambrian Explosion". Integrative and Comparative Biology 43 (1): 166–177. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.166.

- ↑ Conway Morris, Simon (2008). "A Redescription of a Rare Chordate, Metaspriggina Walcotti Simonetta and Insom, from the Burgess Shale (Middle Cambrian), British Columbia, Canada". Journal of Paleontology 82: 424. doi:10.1666/06-130.1.

- ↑ Xiao, Shuhai; Steiner, M; Knoll, A. H; Knoll, Andrew H. (2002). "A Reassessment of the Neoproterozoic Miaohe Carbonaceous Biota in South China". Journal of Paleontology 76: 345–374. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2002)076<0347:MCCIAT>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 Harvey, T.H; Butterfield, N.J (April 2008). "Sophisticated particle-feeding in a large Early Cambrian crustacean". Nature 452 (7189): 868. doi:10.1038/nature06724. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 18337723. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v452/n7189/full/nature06724.html. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Harvey, T.P.H. (2007). "The ecology and phylogeny of Cambrian pancrustaceans". In Budd, G.E.; Streng, M.; Daley, A.C.; Willman, S.. Programme with Abstracts. 51. Palaeontological Association Annual Meeting. Uppsala, Sweden. http://downloads.palass.org/annual_meeting/2007/palass2007_programme_abstracts.pdf.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Droser, Mary L; Finnegan, Seth (2003). "The Ordovician Radiation: A Follow-up to the Cambrian Explosion?". Integrative and Comparative Biology 43 (1): 178. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.178.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 Erwin, D.H., and Davidson, E.H. (July 1, 2002). "The last common bilaterian ancestor". Development 129 (13): 3021–3032. PMID 12070079. http://dev.biologists.org/content/129/13/3021.full. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ↑ Bengtson, S. and Zhao, Y. (17 July 1992). "Predatorial Borings in Late Precambrian Mineralized Exoskeletons". Science 257 (5068): 367. doi:10.1126/science.257.5068.367. PMID 17832833.

- ↑ Chen, J.Y., Oliveri, P., Davidson, E. and Bottjer, D.J. (2004). "Response to Comment on “Small Bilaterian Fossils from 40 to 55 Million Years Before the Cambrian”". Science 306 (5700): 1291. doi:10.1126/science.1102328. PMID 15550644.

- ↑ doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2000.00077.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Erwin, D.H. (2007). "Disparity: Morphological Pattern And Developmental Context". Palaeontology 50: 57. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00614.x.

- ↑ Lofgren, Andrea Stockmeyer; Plotnick, Roy E.; Wagner, and Peter J. (2003). "Morphological diversity of Carboniferous arthropods and insights on disparity patterns through the Phanerozoic". Paleobiology 29: 349. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2003)029<0349:MDOCAA>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Towe, K.M. (1970-04-01). "Oxygen-Collagen Priority and the Early Metazoan Fossil Record" (abstract). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 65 (4): 781–788. doi:10.1073/pnas.65.4.781. PMID 5266150. PMC 282983. http://www.pnas.org/content/65/4/781.abstract.

- ↑ Catling, D.C; Glein, C.R; Zahnle, K.J; McKay, C.P (June 2005). "Why O2 Is Required by Complex Life on Habitable Planets and the Concept of Planetary "Oxygenation Time"". Astrobiology 5 (3): 415–438. doi:10.1089/ast.2005.5.415. ISSN 1531-1074. PMID 15941384.

- ↑ PMID 19200141 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Hoffman, P.F., Kaufman, A.J., Halverson, G.P., and Schrag, D.P. (28 August 1998). "A Neoproterozoic Snowball Earth" (abstract). Science 281 (5381): 1342–1346. doi:10.1126/science.281.5381.1342. PMID 9721097. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/281/5381/1342.

- ↑ de Rosa, R., Grenier, J.K., Andreeva, T., Cook, C.E., Adoutte1, A., Akam, M., Carroll, S.B. and Balavoine, G. (June 1999). "Hox genes in brachiopods and priapulids and protostome evolution". Nature 399 (6738): 772. doi:10.1038/21631. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 10391241.

- ↑ Newman, S.A. and Bhat, R. (April 2008). "Dynamical patterning modules: physico-genetic determinants of morphological development and evolution". Physical Biology 5 (1): 0150580. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/5/1/015008. ISSN 1478-3967. PMID 18403826.

- ↑ Parker, Andrew (2003). In the Blink of an Eye. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Perseus Books. ISBN 0738206075. OCLC 52074044.

- ↑ McCall (2006). "The Vendian (Ediacaran) in the geological record: Enigmas in geology's prelude to the Cambrian explosion". Earth-Science Reviews 77: 1. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.08.004.

- ↑ Dawkins, R. and Krebs, R.J. (September 21, 1979). "Arms races between and within species". Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences Series B 205 (1161): 489–511. doi:10.1098/rspb.1979.0081. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0080–4649(19790921)205%3A1161%3C489%3AARBAWS%3E2.0.CO%3B2–1.

- ↑ Peterson, K.J., McPeek, M.A., and Evans, D.A.D. (June 2005). "Tempo and mode of early animal evolution: inferences from rocks, Hox, and molecular clocks" (abstract). Paleobiology (Paleontological Society) 31 (2 (Supplement)): 36–55. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0036:TAMOEA]2.0.CO;2. http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/31/2_Suppl/36.

- ↑ Ancient macrofossils unearthed in West Africa.

- ↑ Solé, R.V., Fernández, P., and Kauffman, S.A. (2003). "Adaptive walks in a gene network model of morphogenesis: insights into the Cambrian explosion". Int. J. Dev. Biol. 47 (7): 685–693. PMID 14756344.

- ↑ Erwin, D.H.; Valentine, J.W. and Sepkoski, J.J. (November 1987). "A Comparative Study of Diversification Events: The Early Paleozoic Versus the Mesozoic". Evolution 41 (6): 1177–1186. doi:10.2307/2409086. PMID 11542112. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2409086. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ↑ Valentine, J.W. (April 1995). "Why No New Phyla after the Cambrian? Genome and Ecospace Hypotheses Revisited" (abstract). PALAIOS 10 (2): 190–194. doi:10.2307/3515182. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0883–1351(199504)10%3A2%3C190%3AWNNPAT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-H#abstract.

- ↑ Seilacher, A., Bose, P.K. and Pflüger, F. (1998). "Animals More Than 1 Billion Years Ago: Trace Fossil Evidence from India" (abstract). Science 282 (5386): 80–83. doi:10.1126/science.282.5386.80. PMID 9756480. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/282/5386/80. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ↑ Budd, G.E.; Jensen, S. (2000). "A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla" (abstract). Biological Reviews 75 (02): 253–295. doi:10.1017/S000632310000548X. http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S000632310000548X. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ↑ Lieberman, B. (2003). "Taking the Pulse of the Cambrian Radiation". Integrative and Comparative Biology 43 (1): 229–237. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.229. http://icb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/43/1/229.

External links

- The Cambrian “explosion” of metazoans and molecular biology: would Darwin be satisfied?

- On embryos and ancestors by Stephen Jay Gould

- "The Cambrian “explosion”: Slow-fuse or megatonnage?" (Scholar search). http://www.pnas.org/content/97/9/4426.full.

- The Cambrian Explosion – In Our Time, BBC Radio 4 broadcast, 17 February 2005

- Utah's Cambrian life – new (2008) website with good images of a range of Burgess-shale-type and other Cambrian fossils.